Peruvian Coffee - LAS ORQUIDEAS Farm [Caturra Variety] Coffee Bean Growing Information Introduction

Professional coffee knowledge exchange, more coffee bean information, please follow Coffee Workshop (WeChat official account: cafe_style)

Peru Coffee - LAS ORQUIDEAS Farm [Caturra Variety] Coffee Bean Cultivation Information Introduction? How Does Peru Coffee Taste?

Farm Las Orquídeas is located in the Triunfo district, belonging to the Jalca Grande district - Chachapoyas province - Amazonas region, two and a half hours from Rodriguez de Mendoza, at an altitude of 1950 masl. Its total area is 15 hectares, of which 4 hectares are dedicated exclusively to coffee cultivation.

In 2012, Mr. Tito Huaman Hall achieved victory in his search for land suitable for coffee cultivation. This is how his estate "Las Orquídeas" began implementation that same year, and to date, the owner has managed to produce one of the best coffees in the region with great satisfaction.

Orquídeas means "orchid" in Spanish.

Farm Information

Region: AMAZONAS

Harvest Year: 2017

Harvest Months: May to July

Farm Name: LAS ORQUIDEAS

Altitude: 1950 masl

Coffee Mill Type: Washed

Flowering: From May to July

Soil Type: Clay

Temperature/Average Temperature: 17°C

Average Rainfall: 2500 mm

Type of Shade Trees: LEGUMES

Shade Density: 15%

Types of Plants and Animals Present: Orchids, SAMCAPILLA, GALLITO DE LAS ROCAS, LOROS

Fertilization Method: Organic fertilizer

Environmental Protection Measures: [Not specified]

Processing Type: Washed

Fermentation Type: 12 to 18 hours

Variety: Caturra

Certification: Organic

History of Coffee in Peru

Coffee was introduced to Peru in the mid-18th century through the neighboring country of Ecuador, but commercial exports did not begin until the late 19th century. Production only increased significantly after the 20th century, when Peru defaulted on loans to the British government and saw more than two million hectares transferred to British ownership (under the name "Peruvian Nation") as repayment. A quarter of this was used for agricultural production, including coffee, at which point the export trade began in earnest.

Throughout Latin America, the early days of Peruvian coffee production were characterized by large concentrations of land in the hands of wealthy (mostly European) elites; however, when workers migrated from other regions of Peru (such as the highlands) to these farms to provide labor, they began to open their own independent shops - quite easily, as land was abundant.

In the post-war years, as British companies left, these small-scale "campesino" producers remained. This trend was consolidated in the 1950s and 1960s, as the Peruvian government engaged in land reform and encouraged coffee cultivation as part of a series of socioeconomic development measures; this crop, very suitable for small farmers, led to a demographic change in the country's coffee production, with small-scale indigenous farmers now responsible for most of the country's production. Early military dictatorships in the mid-20th century further supported this image through the partial co-operativization of the country's producers - arguably one of the only potentially positive legacies of this era. During the period 1970-1980, under the quota system of the International Coffee Agreement, profits were successfully channeled to state-supported coffee cooperatives, which were responsible for exporting 80% of the product in the 1970s. Of course, much of the profit flowed into government coffers, and while supporting cooperatives, this situation also fostered complacency, with few operational improvements during this period.

Fujimori's structural adjustment policies in the 1980s further weakened autonomy and capacity building, and after the economic crisis, the rise of the Shining Path and the subsequent violence had a considerable impact on coffee cultivation (in fact, on all agriculture). Coffee production required significant capital and labor investment, and many farmers migrated from rural areas to relatively safer urban environments, causing the collapse of trade networks (already fragile).

This downward trend was largely reversed in the mid-to-late 1990s with the shift to "ethical" coffee. Despite historically low prices, "solidarity" networks prioritized trading fairly, ecologically-friendly coffee, driving a coffee boom in Peru. In fact, the area dedicated to coffee cultivation increased from 163,000 hectares in 1995 to 215,000 hectares in 2005. This made Peru the only Latin American country, besides Brazil, that defied the production decline during the period of historically low prices. Specialty imports (including certified coffees) began in 1997 and gradually increased, contributing to Peru's current position as the world's seventh-largest producer. However, exports fell by more than 40% in the 2013/14 and 2014/15 harvest years (production fell by more than 30%), largely due to the impact of coffee leaf rust, which has a significant impact in this country where coffee is grown without pesticides or fungicides. Peru is currently the world's largest exporter of organic coffee, with approximately 90,000 hectares of organic certification. This is mainly due to smaller producers' lack of resources for investment in chemical inputs; however, after the coffee leaf rust crisis, it is difficult to say how long this will last.

Today, approximately 223,000 Peruvian families have committed about 425,000 hectares to coffee production, and another 300,000+ people depend on the coffee industry in some way. Production remains concentrated in the Cajamarca region in the north of the country, where half of the nation's coffee is grown. More than 70% of this is Typica, followed by Caturra (20%), and other varieties (10%). Other regions also produce coffee, such as Cusco and Junín in the south.

As mentioned earlier, Peru's production today is very small, with an average farm area of less than 3 hectares. Associated with this structure are problems typically related to small-scale producers in Latin America, such as difficulty accessing credit and managing inefficient production and processing. Cooperatives help producers reduce risk and provide access to resources necessary for harvesting, and currently, most of Peru's coffee is collected from small farms and then bulked together before being milled and sold through these cooperatives, with the largest representing up to 2,000 farmers and 7,000 hectares. However, although many of these cooperatives place great importance on improving processing, productive inputs remain a blind spot. While this is changing, the slow progress in focusing on production and quality, combined with the lack of existing infrastructure (processing and transportation), gives Peru a poor reputation.

Nevertheless, with twenty-eight cited microclimates, Peru has the potential to improve regional coffee characteristics, as a quarter of its coffee is grown between 1,200 and 2,000 meters, and there is great potential to develop greater traceability and identify small specialty producers, which Mercanta is currently working on.

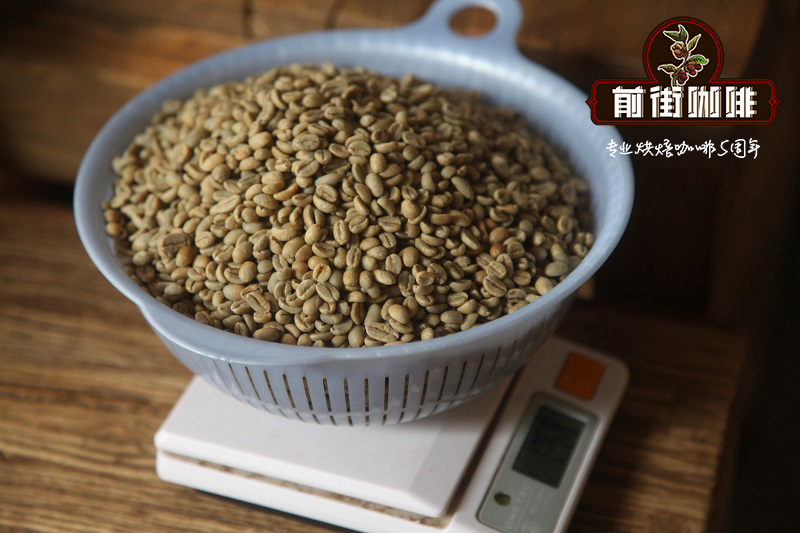

FrontStreet Coffee Recommended Brewing Method for Peru Coffee?

Dripper: Hario V60

Water Temperature: 88°C

Grind Size: Fuji Royal grinder setting 4

Brewing Method: Water-to-coffee ratio 1:15, 15g of coffee, first pour 25g of water, let bloom for 25 seconds, second pour up to 120g then pause, wait until the water level in the coffee bed drops to half before continuing to pour, slowly pour until reaching 225g, extraction time around 2:00

Analysis: Using a three-stage brewing method to clearly distinguish the flavors of the coffee's front, middle, and back sections.

Important Notice :

前街咖啡 FrontStreet Coffee has moved to new addredd:

FrontStreet Coffee Address: 315,Donghua East Road,GuangZhou

Tel:020 38364473

- Prev

Coffee Processing Methods | Tree-Drying Process | Flavor and Characteristics of Tree-Dried Coffee

Professional coffee knowledge exchange For more coffee bean information please follow Coffee Workshop (WeChat public account cafe_style) Tree-Drying Process Some coffee farmers intentionally allow coffee cherries to dry naturally on the tree (dried on the tree) or Tree Dry-Process (also translated as tree-dried fruit, in-cluster drying) coming from beans harvested at a late stage, after the

- Next

Introduction to Single-Origin Peruvian Coffee Beans - Caturra from Agmer Colorado Coffee Farm

Professional coffee knowledge exchange and more coffee bean information, please follow Coffee Workshop (WeChat official account: cafe_style). Introduction to Single-Origin Peruvian Coffee Beans - What are the flavor and profile of Caturra from Agmer Colorado Coffee Farm? Produced from Arabica trees of red and yellow Caturra varieties by Gilmer Crdova of Agmer Colorado Farm. This coffee in 2017

Related

- How to make bubble ice American so that it will not spill over? Share 5 tips for making bubbly coffee! How to make cold extract sparkling coffee? Do I have to add espresso to bubbly coffee?

- Can a mocha pot make lattes? How to mix the ratio of milk and coffee in a mocha pot? How to make Australian white coffee in a mocha pot? How to make mocha pot milk coffee the strongest?

- How long is the best time to brew hand-brewed coffee? What should I do after 2 minutes of making coffee by hand and not filtering it? How long is it normal to brew coffee by hand?

- 30 years ago, public toilets were renovated into coffee shops?! Multiple responses: The store will not open

- Well-known tea brands have been exposed to the closure of many stores?!

- Cold Brew, Iced Drip, Iced Americano, Iced Japanese Coffee: Do You Really Understand the Difference?

- Differences Between Cold Drip and Cold Brew Coffee: Cold Drip vs Americano, and Iced Coffee Varieties Introduction

- Cold Brew Coffee Preparation Methods, Extraction Ratios, Flavor Characteristics, and Coffee Bean Recommendations

- The Unique Characteristics of Cold Brew Coffee Flavor Is Cold Brew Better Than Hot Coffee What Are the Differences

- The Difference Between Cold Drip and Cold Brew Coffee Is Cold Drip True Black Coffee